Close-ups

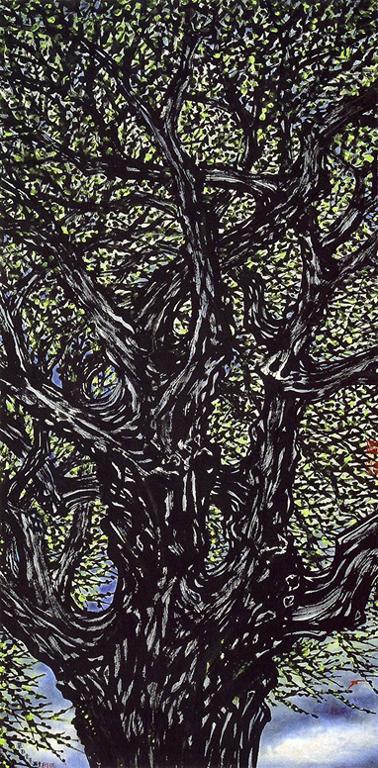

(L) Lo Ch'ing, Ten thousand green buds: the explosion of spring, 2005, 137 x 69 cm, ink painting

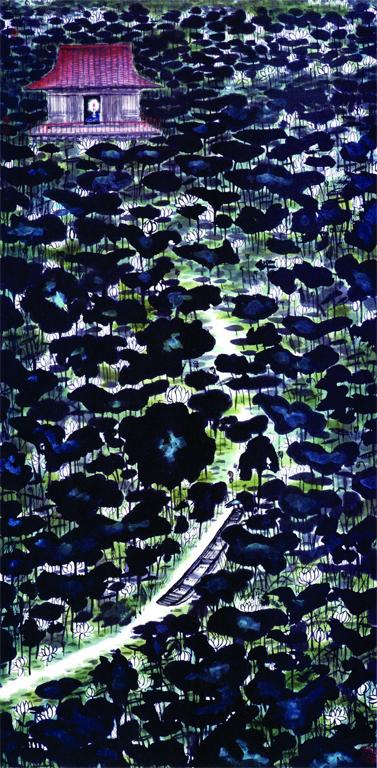

(R) Lo Ch'ing, One red candle and ten-thousand white lotus, 1999, 137 x 69 cm, ink painting

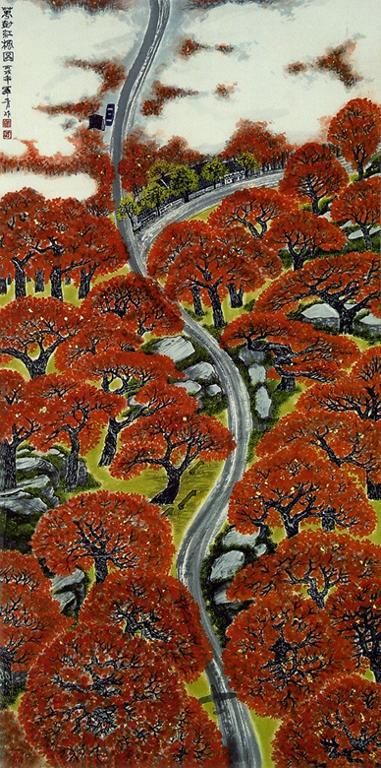

(L) Lo Ch'ing, Ten thousand red leaves: a metaphysical fire, 2006, 137 x 69 cm, ink painting

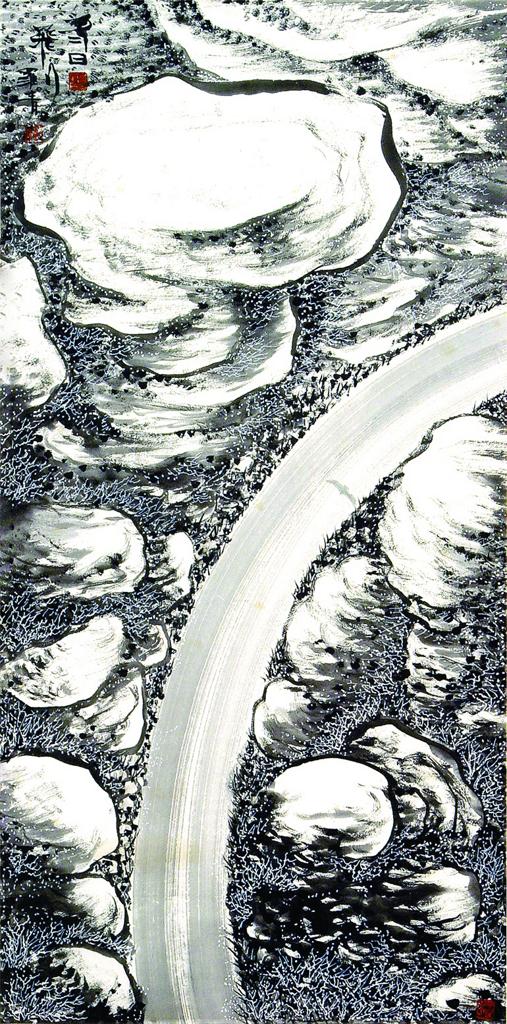

(R) Lo Ch'ing, Wintry flight, date unknown, 137 x 69 cm, ink painting

Lo Ch’ing carefully adopts the conventional elements of a Chinese literati painting and augments his own memoirs of each season with the use of rich color and symbolic objects. Chinese painter and calligrapher Zhao Mengfu (1254-1322) illuminates the conventional setting of a Chinese landscape in his poem on Dong-Yuan’s Riverbank:

How the mountains peaks are gray and white,

With gentle mists encircling their waist.

Blocking the sun, the high mountains,

Dark and obscure, are heavy with rain.

A stream, meandering through the valley,

Disappears into distant sandy marshland.

Here macaques and gibbons thrive,

And ducks and wild geese gather.

Who is that gentleman who lives in seclusion,

Keeping company with fragrant grasses?

When he sings, the forest quivers with the sounds of autumn.[1]

As Zhao Mengfu elaborates, a typical Chinese literati landscape is composed of seven parts: 1) mountains, peaks, hills, rocks, pebbles, 2) trees, groves, woods, grass, 3) rivers, creeks, waterfalls, lakes, ponds, 4) clouds, 5) cottages, boats, bridges, 6) figures, and 7) colophons and seals.[2] Lo Ch’ing carefully re-arranges some of the conventional components and removes the high, flat, and deep distant-view vistas from the scenery. Instead, he presents close-up views cropped out from a large scenery: a old tree seen from a lower angle view with lush green leaves for spring, densely grown lotus plants with a remote cottage for summer, burning red trees for autumn lining along the modern asphalt roads, and icy roads with rocks covered with snow for winter. All of these subjects are carefully selected for their cultural reference. After selecting the subjects, Lo carefully selects his favorite spot and reorganizes the space to show the features he adored most, adding sumptuous colors combined with traditional ink.

The colors are not imaginary ones, but instead reveal the essence and symbolic meanings of the object. In the interview with Asian Art Newspaper in October 2014, Lo said, “I try to revive and combine the Chinese color tradition with the Chinese ink tradition. This is why my paintings are so colorful. These colors have their roots in Han-dynasty paintings, in mirror paintings, and can even be traced back to neo-lithic times.” Lo carefully picks the essential color theme for each season in order to convey the differing times of year and admires the inner essence of his own spiritual mind: green for spring, deep blue for summer, red for autumn, and white for winter.

[1] Zhao Mengfu, Songxuzhai ji, juan 2:12a. Quote from Wen C. Fong, Art as History: Calligraphy and Painting as One (Princeton, Princeton University Press, 2016), 208.

[2] Lo Ch’ing, “The Chinese Language and Chinese Landscape Painting,” Studies in English Literature & Linguistics (May, 1987): 92-93.