Introduction

"In a landscape painting, a Chinese painter will never stand at a fixed point to look at the mountain because the view is limited. You cannot say there is only foreground, middle ground, and background, then all the mountains will look the same. Then, the painter is required to travel to the mountain, and then after he gets familiar with it, then he can choose his favorite spot and reorganize the space and the composition to show the features he enjoyed most into the painting. Consequently, the painting itself is a sort of portrait of the artist, in a way."

—Lo Ching, 2015

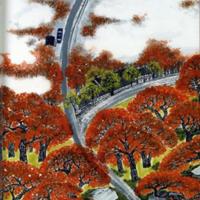

As art historian Eugene Y. Wang argues, traditionalism and modernism, East and West, radicalism and conservatism tend to converge or collide in Chinese contemporary art as a means to address the historical complexity underlying Chinese modernist aspiration. The Taiwanese poet-painter Lo Ch’ing adds to or disassembles the elements of Chinese traditional landscape paintings and transforms this tradition into a contemporary one. He claims to a return to the ancient masters of Chinese ink painting, but also contributes affective responses to the cyclical changes of the four seasons by attending to his own mental encounter with these landscapes.

Lo’s seasonal landscapes bear a juxtaposition of traditional brush strokes with newly created ones, conventional seasonal subjects with arbitrarily cropped views and colorful touch, and meteoric rocks floating within a traditional landscape setting. Most of his paintings develop imagery that attempts to adequately visualize the overall mood of each season, which will be further investigated in the following thematic sections: the vignettes, close-ups, and the metaphysical landscapes with rocks. One of his earlier poems Ode to the Southwest Wind exemplifies Lo’s feelings on the cyclical change of the seasons in a glance:

Ode to the Southwest Wind

In the spring the southwest wind has a fine hand

Especially fine in brushstrokes of air and light

The waves of the East China Sea offer testimony:

Putting time in motion for its ink, dipping into moonlight for water

The face of sun is its inkstone, flashes of lightning its brush

Unrolling long handscrolls of blue sky

Of limitless grasslands, and unrolling

The sea

After you have seen a lone bird fly in and out of the deep woods

Then you really understand calligraphy

The tip of its brush strikes –

It is filled with inky clouds and snowy splashes

In the depths dragons are startled, stones suddenly awakened

The power of the brush moves-

Autumn leaves pile up and scatter around the world, blown on

Running and fighting over the undulating ridges that fill the sky

A dot and a dash form a lonely valley

A hook and stroke set off mountain floods

Agitated it looks like sheets of rain across the ground

Relaxed it resembles the sweet growth of spring grasses

Leaning over like grain collapsing under full and heavy ears

Each intention starts out from the northern sea, thoughts gather together in the southwest reaches

And nonchalantly it writes the two rivers

Writes them into a long crazy cursive couplet full of feeling

It might either welcome the fog with open arms

Or bring together the mist and clouds

According to its inner desires

Sometimes the elbow flies, or the stylus runs

Releasing the clouds and setting off the rain

Occupying the west of west in the starry sky, it departs

But September

Offers this final evaluation:

It is like a taste of entangled misfortune

A brush with the arctic cold

After the leaves have fallen

And the waves flattened out

The depth of its calligraphic style

Is as the sea, deep

—Lo Ch’ing, November 1969