Introduction

Travels and travelers have a rich history in Chinese painting and poetry. As long ago as the Northern Song Dynasty of the 10th-11th centuries, landscape paintings have alluded to the purposeful movement of a human subject from one space to another—perhaps near, perhaps distant, and perhaps ultimately unreachable.[1]

Indeed, the composition of landscape painting was dependent on travel. An artist would not choose a single, stationary viewpoint for painting a mountain. Instead, he would venture up, around, and into the mountain, observing it from all angles. After studying the landscape in such a manner, the painter would retreat to his home and invent his painting from memory. The resulting image would convey an impression of the mountain informed by the artist’s own emotions and reflections on the experience.

To scholarly “literati” artists, a landscape painting’s meaning reaches far beyond the aesthetic enjoyment of natural beauty. It is inflected with the mood of the painter and it inevitably resonates with the long tradition of landscape painting in China, referencing other artists through calligraphic style, color choice, or iconography. It is the quintessential “art-historical art.”[2] Although static, and often empty of human figures, this intentionally subjective approach to landscape implies longer narratives of movement and contemplation.

The Taiwanese artist Lo Ch’ing (b. 1948) is deeply engaged with past traditions of mainland Chinese literati poetry and painting, but his works are firmly located in the contemporary world—a post-modern world. They reveal a thoughtful, yet playful engagement with the syntax of images and the construction of meaning. Lo Ch’ing’s paintings include many venerable symbols: mountains, winding paths, birds, plum blossoms, and persimmons. However, he is invested in integrating a literati approach to landscape with fresh symbols of the contemporary world. His paintings also include asphalt, cars, airplanes, and even UFOs.

This new visual vocabulary entrenches both the painting and the viewer in postmodernity. Lo Ch’ing raises new questions about the practice of landscape painting and the postmodern individual’s relationship with the natural world.

This is most evident in Lo Ch’ing’s series of paintings titled Homage to Fan Kuan’s Travelers Amid Mountains and Streams. The painter-poet Fan Kuan (c. 990-1030 CE) is one of the most honored painters of the Northern Song period and Chinese landscape painting more broadly. His works are largely known through commentaries by later Chinese scholars, but in 1958 an extant work in the National Palace Museum in Taipei was authenticated as a Fan Kuan original. Known as Travelers Amid Mountains and Streams, this hanging scroll depicts tiny human figures against a monumental and forbidding mountain peak. Separated from the middle-ground by creeping mist, the mountains appear almost unattainable. Far below, nestled in the valley, we see a farmer with a herd of donkeys. He has left a small cluster of homes and follows an easy path along the low-lying streams, rather than venture into the mountainous distance.[3] The painting resonates on many levels. It conveys the majestic beauty of the mountains; it follows the story of the farmer traversing the countryside; and it juxtaposes that farmer against the painter himself, Fan Kuan, who was known to be a hardy mountain man.[4] Perhaps we are meant to see the adventurous Daoist painter reflected in the mountains themselves.

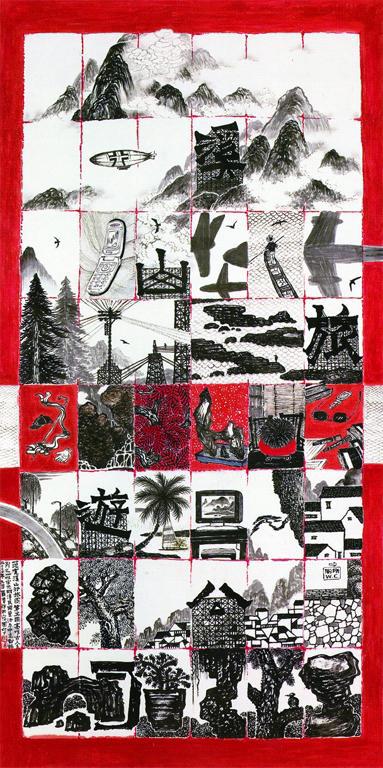

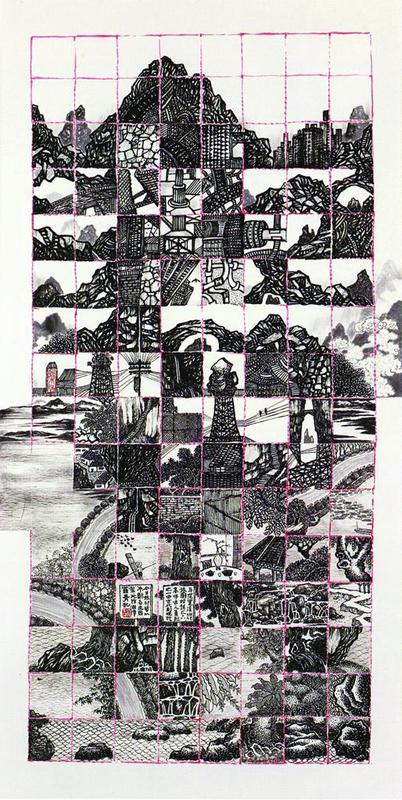

By contrast, Lo Ch’ing has re-envisioned the impact of the mountains in his Homage series. In No. 5 and No. 6 of the series, the mountain vista has been left intact—a distant destination beyond the turmoil of daily life. However, the lower three-quarters give way to the jumbled elements of human settlement, travel, and mass communication. He has fractured the composition into dozens of square segments, interspersing natural elements like mountain peaks, clouds, trees, streams, and rocks, with asphalt roads, power lines, airplanes, zeppelins, houses, and television sets.

The Homage series asks us to consider the ongoing relationship between humanity and nature. Do these aspects of contemporary life separate us from nature, or do they facilitate our experience of nature? How is our experience of the mountains different than that of Fan Kuan’s farmer?

Lo Ch’ing suggests that we are moving, always moving, against the still backdrop of the horizon.

[1] Richard M. Barnhart, Three Thousand Years of Chinese Painting (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1997), 92-93.

[2] Jerome Silbergeld, Chinese Painting Style: Media, Methods, and Principles of Form. (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1982), 21.

[3] Barnhart, Three Thousand Years of Chinese Painting, 102-103.

[4] Ibid.