The landscape speaks

In past Chinese literati paintings, the landscape and non-human figures are often understood as metaphors for the painter's own thoughts and emotions. Although this approach is present in many of Lo Ch'ing's landscape paintings, some of his works question this paradigm. He includes man-made thoroughfares, but human narratives are de-emphasized. Instead, Lo Ch'ing imagines the subjective experiences of mountains, trees, and houses situated within the landscape. As he considers the relationship between humanity and nature, he acknowledges that these entities are inevitably symbiotic.

"...Yellow Mountain, Huangshan--it's an ideal or sacred mountain for all the Chinese landscape painters. In the past they had to spend a week or two from the bottom of the mountain to climb to the top. Now it's only, by cable car, 25 minutes and you reach the peak or the most scenic spots of the mountain area."

-Lo Ch'ing, 2015

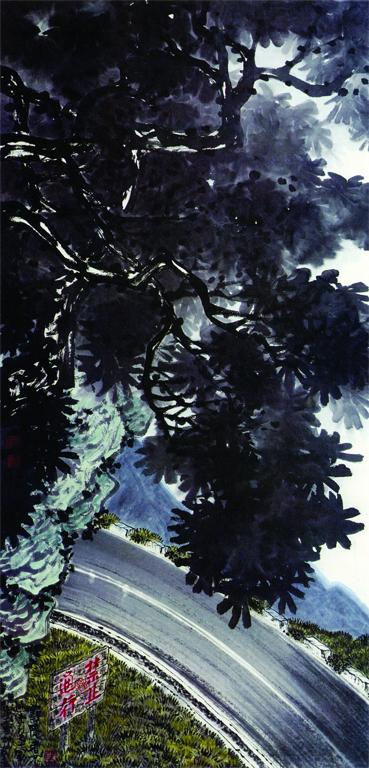

As in Two pavilions: past and present, Lo Ch'ing has placed the viewer on the mountainside, suggesting a journey in progress. However, the path is blocked. Rocks and tree branches interrupt a double-laned road, while a weather-beaten, wooden sign warns travelers to stay away. Read in conjunction with the humorous title—"No recluse, please!"—the sign seems to speak for the wilderness itself. Wanderers and hermits are not welcome. Altough modern transportation has made travel easy, the mountain rejects any prospective settlers. The road's center line hints at a prosaic contemporaneity, detracting from any sense of timelessness or transcendence in this mountain scene. Travelers must adjust their expectations.

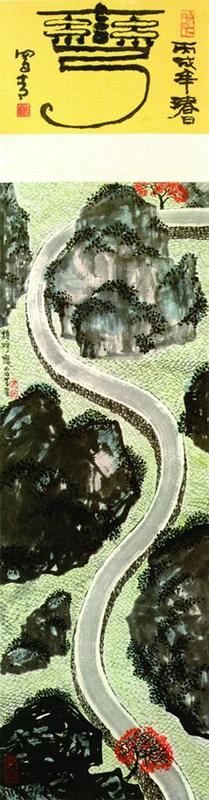

Viewed from high above, the asphalt road seems more organic than manufactured. We see that the road is fully integrated with its surroundings. It wiggles across the landscape like a snake, curving around jagged, rocky outcroppings that could obstruct it. There are no human or animal bodies in sight: just rocks, road, grass, and trees. However, Lo highlights two trees in particular: one at the very bottom of the scroll and one at the very top, both crowned with bright red leaves.

The title “Red Trees’ Blues” suggests that these trees are sad or worried. Lo prods us to study the painting, to search for the cause of their emotion. Are they unhappy about the paved intrusion into the landscape?

While the road is an important element in the painting, we should not assign it such a simple ecological meaning. The positions of the trees help guide our interpretation. At the bottom, the red tree seems to reach out and away from its mountain perch, overlapping with the surface of the road. The road then moves our eyes upward, echoing the features of the landscape, before leading us to the red tree at the top of the painting. It is more reserved, tucked away behind a mountain.

The road connects these two red trees which are otherwise separated by a vast, rocky landscape. The trees are yearning for one another, but their plight is hopeless. Even though they are linked by the asphalt road, which implies movement through space, they are rooted in place.

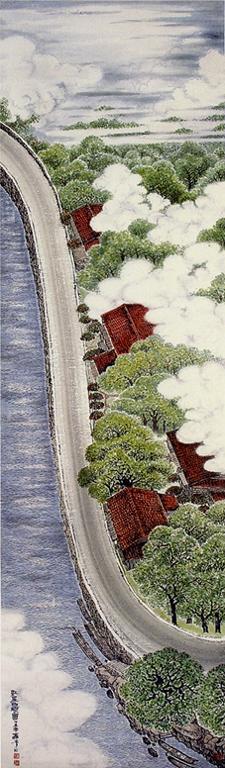

What are the dreams of red roofs? As with Red Trees’ Blues, we are encouraged to anthropomorphize non-human subjects, imagining their thoughts and feelings.

Here, we see the asphalt road in close dialogue with human dwellings. The red-roofed houses occupy their own, static realm between the pavement and the clouds. To the left of the houses, the strong, curving brushstrokes of the road suggest the possibility of rapid movement from one settlement to another. In contrast, the soft clouds float slowly and freely above the houses.

In most of Lo Ch’ing’s road paintings, the highway is the guiding symbol of movement through a landscape. However, in this painting, the movement of the road is contrasted with the movement of the clouds. It recalls "Two pavilions: past and present," where the road is restricted despite its speed and efficiency.

Do the houses dream of traveling the road, or do they dream of traveling like clouds? Using the red roofs as an unusual focus for meditation, Lo considers humanity’s relationship with the natural world. We can drive through the landscape on a road, or soar among the clouds in an airplane, but we are always travelers, always temporary, never still.