Works

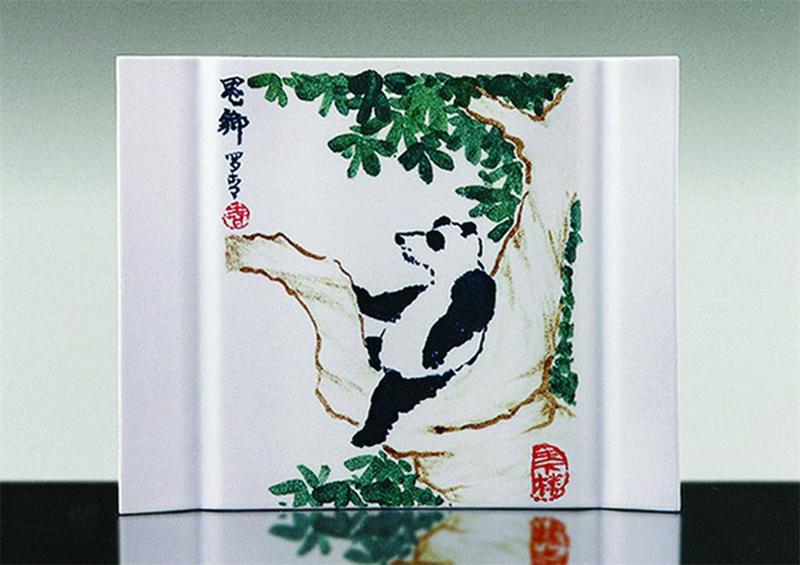

Lo Ch'ing explains that "as an endangered species, on the edge of extinction, the panda is very much like the Confucian gentleman. Because in the 20th century the Confucian scholar or gentleman becomes a joke—he can't survive." The figure of the lone panda appears frequently in Lo Ch'ing's recent painting, especially in a series of ceramic works from 2012. Sometimes the panda is absorbed in eating bamboo shoots or, as here, sits thoughtfully and ponders its place (and perhaps also its uncertain survival) in the contemporary global context. The emotion named by the English title of the work, Nostalgia, emphasizes the degree to which the panda exists in a disjointed space and time, thinking of a home that exists only in the past—a home that might be constructed anew but never regained.

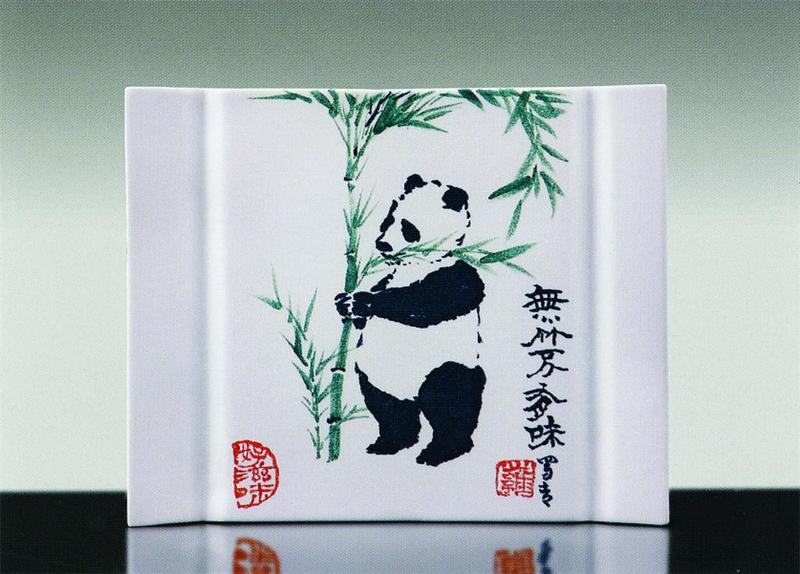

The panda's association with the Confucian gentleman, for Lo Ch'ing, also comes from its diet of bamboo. He says, "Bamboo is a very typical symbol of the Chinese Confucian gentleman, because—like pine trees—it stays green even in the snow." The panda's diet is not merely connected to the health of its body (which in turn suggests the fragility of the species in the face of extinction), but also of its soul. Lo's work suggests that the panda—who is also the metaphorical double of the human—faces an ecological situation in which what it eats determines both its material and its spiritual wellbeing. As one of Lo's poems makes clear, the panda "likes to chew bamboo shoots./ It has nothing to do with the gourmet poet/ or the fitness center." In an era when global processes of food trade and production raise new ethical challenges, the processes of nourishing our bodies must also be weighed against their effect on our souls and the souls of the animals with whom we share the Earth.

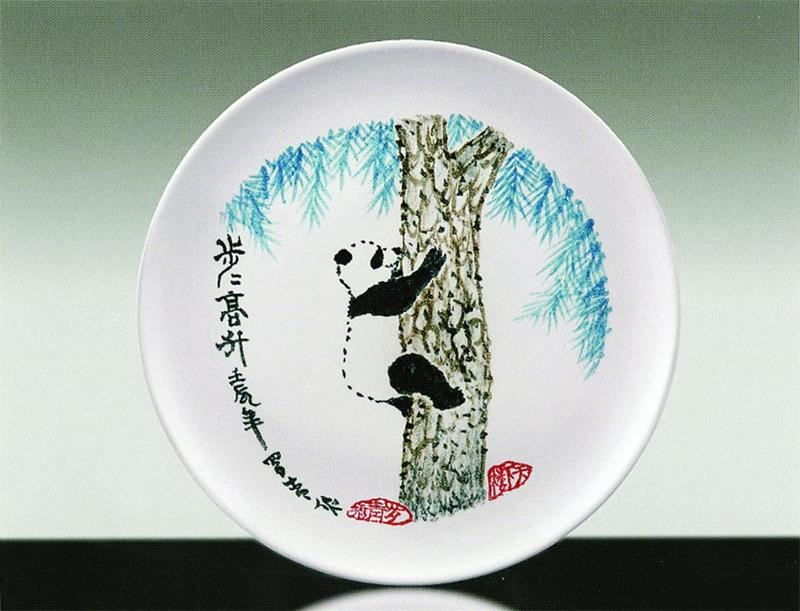

The panda in Lo Ch'ing's Climbing Up Higher and Higher is arrested in a perpetual movement between beginning and end, in a composition that rejects a strict teleological goal. We might imagine this panda as a symbol of our own conflicted present: constantly advancing, but—in any given moment—disconnected from both our roots and our future achievements. In this situation, we are called upon to hold on to the trunk of our tree, to the Earth. The image of the panda, Lo Ch'ing notes, was used in the 20th century by Communist China as a kind of cultural, political, and economic ambassador. Perhaps the time has come to envision the panda —and ourselves—as ambassadors in the process of negotiating a whole new set of uncertain human and environmental relations. Like the panda who climbs the tree, we are now in the middle, sure of where we are going but unsure of what it will look like.

The perceived innocence of the panda, absorbed in eating bamboo shoots, belies the way in which its own endangered status is entwined with the fate of humans in the era of global ecological crisis. As Lo Ch'ing writes in his poem "O' Panda an' Man," speaking from the perspective of panda: "[…] I who am about to become extinct/ being protected and preserved year round/ behind the bars/ have everything to do/ with your life and death/ in the future." Thinking the panda, and through its metaphorical sign the whole constellation of nonhuman entities that inhabit the world, we come face to face with the responsibilities that characterize the Anthropocene.

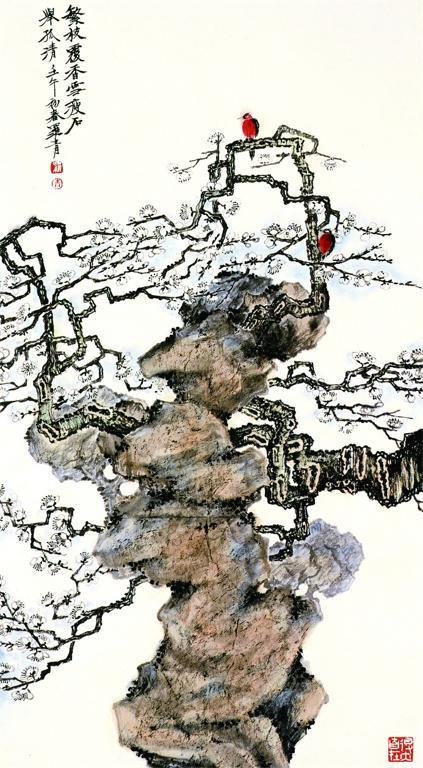

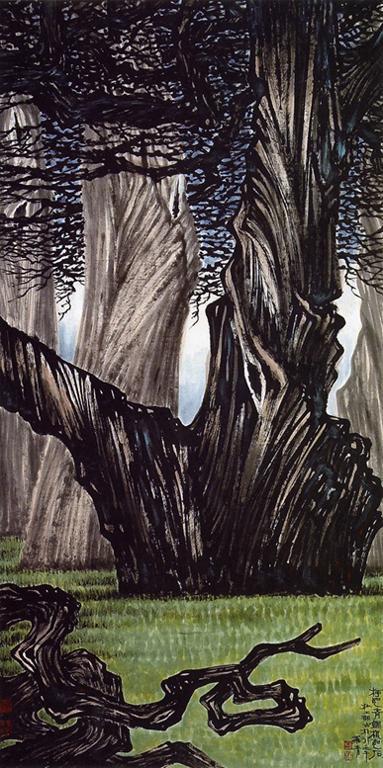

In this painting, the communion of nonhuman entities is expressed not on the affective and contemplative register of nostalgic longing, but in the even more invisible realm of dreams. On the trunk of the knotted and twisted pine tree rests a sleeping crane, and the viewer sees not only this heron but also its dream, in which a great white amorphous form springs out of the tree's nettles, hovering like a swirling cloud in the night sky. The pine tree's dream is illegible to us, and we are left to speculate in turn upon the significance of this dream for the crane. The image that the artist shows us, the crane and its dream, is an image of the fundamental interconnectedness of all things, of a whole world of material and metaphysical relations that escape our notice as we go about our lives.

Chinese ink painting traditionally takes an interest in the imperfect surfaces of trees and rocks: the more aged and twisted the tree, the more craggy and misshapen the rock, the better. These forms and surfaces suggest the resilience of their objects, and they also trace a line between formal abstraction and rich symbolic associations. The intertwining of rock, tree, animal, and language is echoed the title of Complicated Yet Simple and Clear. Lo Ch'ing shows us a world in which the living and non-living, the material and the linguistic, do not just exist side by side but cooperate to produce the meaning we discover in them.

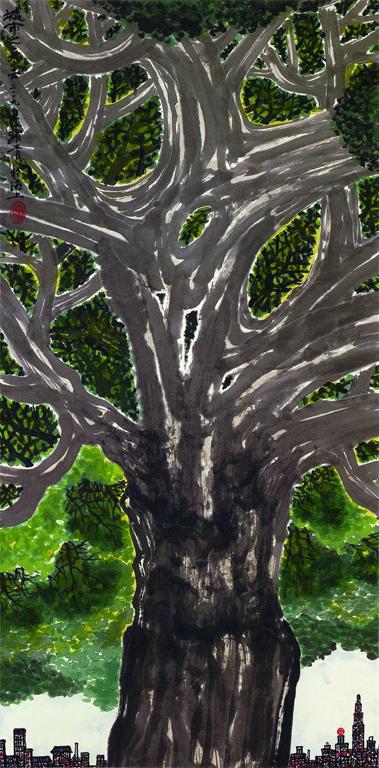

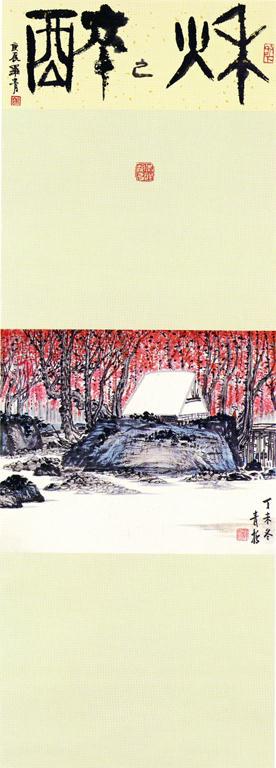

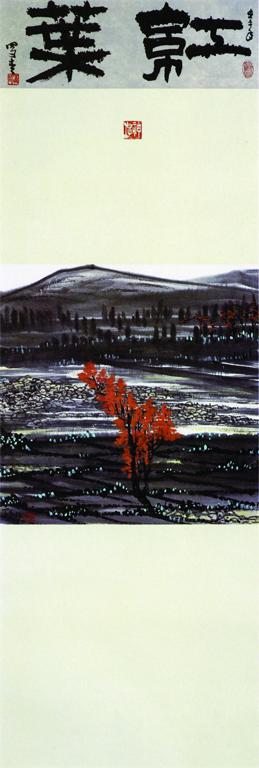

One of the crucial themes of Lo Ch'ing's landscapes is the contradictory coexistence of different times and spaces. We traverse these spaces—visually—in an instant, our eye moving swiftly across the surface of the painting. This velocity mirrors the speed at which, in reality, we likewise move from the timeless and eternal landscapes of the past to the dynamism of the modern city. Our passage between the two is facilitated by cable cars, buses, and airplanes. As Lo Ch'ing notes in an interview, the permeability of time and space experienced by the (post)modern traveler produces a state of schizophrenia, in which we are constantly torn between our past and present. The same schizophrenic emotion might be said to emerge in the landscape itself, in the evolutionary schism between the deep time of old trees and the waxing and waning of human cities—cities that constantly shape and re-shape the horizon of being.

The metaphor of ascent is often present in Lo Ch'ing's work, and not only in his images of pandas climbing trees. Indeed, the ascent is not merely to the treetops, but perhaps even beyond—to the sky, to the reaches of space from which Lo's meteoric rocks descend. Across the world, one of the most recognizable signs of global capitalism's ubiquity is the proliferation of towers: manmade beacons of steel and glass that rise above all natural phenomena. And yet, Lo Ch'ing argues, we can escape from the towers and the cities, can return—if only for a brief time—to the past embodied by the natural world. However fleeting this experience is, it has the power to make us see in new ways, allowing us to catch a glimpse of a different world.

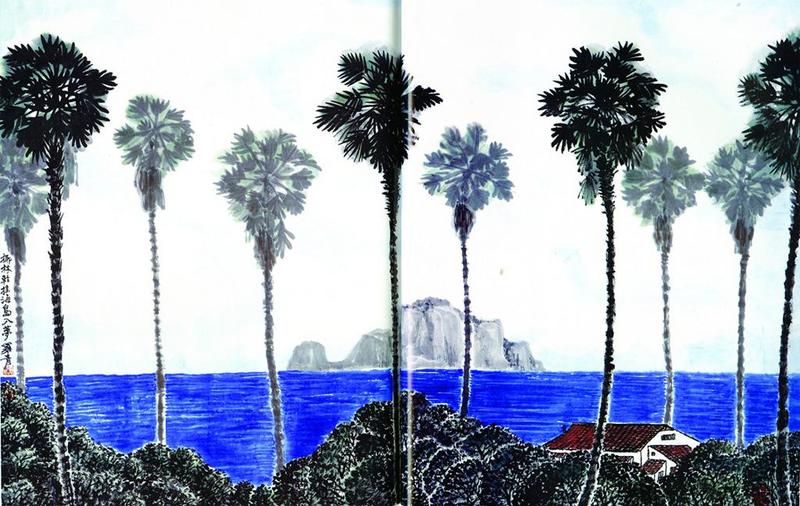

In interviews, Lo Ch'ing explains that one of his contributions to the Chinese landscape tradition is the inclusion of new types of flora, like palm trees. Palms belong to a different geographic landscape than that typically pictured by Chinese ink painting, a tropical landscape like that of Palms Rocking a Small Island Into Dreams. The palm trees, with their long, straight, narrow trunks and clusters of fronds at the top produces a rhythmic aesthetic quite different than, say, the gnarled pine tree, and this rhythmic quality mirrors the poem, written down the left edge of the image like a palm trunk.

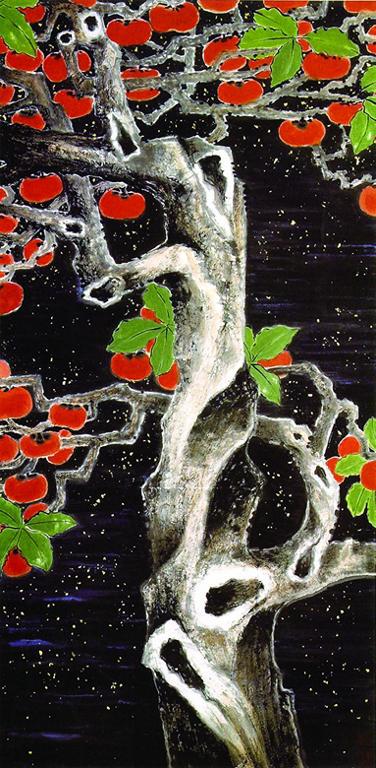

The juxtaposition between (invisible, deep, stone) roots and (visible, twisting, brass) branches echoes a fundamental duality in the life of flora—that between limbs that grow upwards and outwards in meandering paths towards the light of the sun and the roots that tie plants to the nurturing force of the earth, rich with hidden flows of water and minerals. Between the tips of the highest branches and the deep roots below, Lo Ch'ing shows us the gnarled trunk, painted boldly in black ink, emphasizing the duration of the tree's existence connecting extremes—living in a middle space between sky and earth.

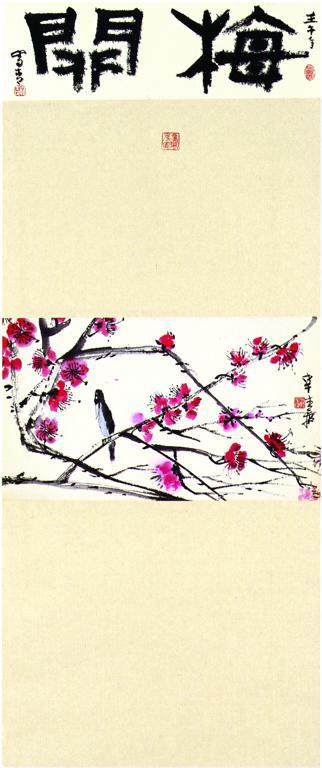

Lo Ch'ing is deeply interested in the way the form of the painted vignette, as developed by Song Dynasty artists, uses the part to suggest the whole (and of course in the way it combines poetic language with image). Here, the smallest signs of change—bright pink blossoms bursting forth and a small bird perched on a branch—herald the all-encompassing change of the season. As in other of his works, here the artist has emphasized a subtle disjuncture in time: the sudden anticipatory moment of the blossom projects both the arrival of spring and references the cycle of the seasons as a whole. In this way, the smallest image contains vast reaches of past and future time even as it draws us into the small details of the world.

The reciprocal character of vision is one of the key aspects of many recent projects endeavoring to theorize the force of nonhuman interactions with humankind. The title of this vignette not only grants the environing forest the power of sight; it also playfully takes up the Chinese aesthetic paradigm whereby a surrounding landscape reflects the characteristics of a figure within it, or vice versa. A symmetry is thereby emphasized between the human presence in the landscape and the way nonhuman actors feel, behave, and appear.

This painting investigates the reciprocal interactions between space, color, and natural phenomena. The tree's leaves are a brilliant red—a color Lo Ch'ing often uses, relying on both its visual potency and its rich associations in (especially contemporary) Chinese history. The vignette also suggests a kind of parallel with Lo Ch'ing's ecologically-minded paintings of pandas, where the panda comes to stand for the possibilities of individuals' enlightened comportment towards the natural world. The lone tree, rooted in its place in the surroundings, has the possibility of affecting all that surrounds it, brightening the dark field and causing us to ponder the connections between our spatial and ethical stance and the environment.

Things Will Be Ripe Like Persimmons When Time Comes extends the temporal pattern of ripening to all entities: coming into fruition is metaphorically generalized. Likewise, time itself becomes an entity that arrives—the right time, the moment of fruition (like the seasons) is something that everything waits for. In the increasingly fast-paced world of global information flows and transnational travel, this time of slow growth and waiting seems almost anathema to us. Like Lo Ch'ing's paintings of roads, the persimmon trees appears without beginning (roots) or end (tips of the branches). The tree's growth expresses the internal flow of time that ripens the persimmons and, like them, all of us—in its own time.

Raino Isto is a Ph.D. student at the University of Maryland, College Park. His research interests include the relationship between history and memory in communist-era Balkan monumentality; animal studies; and the intersections and conflicts of postcolonial theory, post-socialism, and object-oriented ontology.