The Sign of the Panda: Thinking the Nonhuman

It is interesting that one of Lo Ch'ing's statements on the panda seems—on its face—to be a sort of rejection of the spirit of linguistic deconstruction, appearing instead as the assertion of a fundamental nature that is distorted by signs. In the preface to a collection of his paintings featuring pandas, Lo Ch'ing describes the iconization of the panda bear following the World Wildlife Fund's adoption of its image as the organization's logo in the 1960s.[1] In addition to the growth of the panda-image as a symbol of endangered species conservation, Lo Ch'ing also traces the etymology of "Xiong-mao" (bear-cat), the modern Chinese name for the animal—a name which came about following the mislabeling of a taxidermied panda displayed at the Museum of Chung-qing in the 1940s. Lo Ch'ing writes, "From then on, panda has suffered a dissociation of sensibility, its name deconstructed from its nature and its form no longer the echo of its content."[2]

Here, Lo points to a complex rift endemic to the aesthetic and linguistic shift from industrial society into "the information age, … from …structuralist epistemologies into [the] poststructuralist recognition of free-floating signifiers."[3] The panda bear appears in discourse and media respectively as a name ("Xiong-mao") inappropriate to its referent and a sign (the World Wildlife Fund's logo) that far exceeds the content of its referent. (It is no doubt significant that—if the anecdote is accurate—the misleading modern Chinese name for the panda appeared in relation to a taxidermied animal. That is, the name referred—to revert to English etymologies—to the arranging or disposition of skin, of the surface of the animal.) In the end, both the sign and the name seem to tell us little about panda.

One way to read Lo Ch'ing's assertion that "the panda has suffered a dissociation of sensibility" is as a kind of modernist longing for the stability of essences. On this reading, Lo's images of pandas eating bamboo, climbing trees, and socializing represent a naïve belief in the possibility of nature-in-itself in the postmodern era. To borrow the title of one of Lo's works, they would be Nostalgia (2012)—gazing into a past that is now beyond recovery. As tempting as such a reading is, given the occasionally apparent sentimentality of his panda images, it is also forthrightly reductive. And in light of a consideration of Lo Ch'ing's insistence on the postmodern paradigm, such a reading is significantly unconvincing.[4] However, we should ask: Why is it precisely at the intersection of postmodern language and the nonhuman that there suddenly emerges such an apparent discomfort with the dissociation of form and content, of signifier and signified? This discomfort with what the panda has suffered comes, I think, not out of an urge to dismiss or defeat the pervasive dissociation of the postmodern era. Instead, it reveals another aspect of postmodernity that has not been fully investigated in Lo Ch'ing's work: the discovery of the inscrutability of the extra-linguistic world of things, a world not exhausted by the vicissitudes of language in the information age.[5]

Rather than interpreting Lo Ch'ing's paintings of animals (or of plants) either as a retrograde modernist impulse at odds with his postmodern language games, or as a straightforward continuation of Chinese art's rich tradition of representing nonhuman subjects, I propose that his works should be considered from the standpoint of recent trends in object-oriented thinking and ecocritical (or 'green') materialism. This means acknowledging that amongst all things—including animals—"there is something that recedes—always hidden, inside, inaccessible," as Ian Bogost writes.[6] In short, the postmodernist aspect of many of Lo Ch'ing's works lies in their posthumanism. They are committed to thinking and representing a way of being with nonhuman entities that does not privilege the human.

The posthumanist approach does not necessarily jettison anthropomorphism. As Jane Bennett (and Bogost following her) argues, anthropomorphizing can help us to understand the full implications of the otherness of things (be they pandas or bamboo plants) and their power. Anthropomorphizing can "highlight the common materiality of all that is" while "expos[ing us to] a wider distribution of agency" among nonhuman actors.[7] Thus, the lighthearted narratives Lo Ch'ing creates with his pandas are not simply meant to 'humanize' their animal subjects, to suggest that behind their iconic faces, pandas live lives just like we do. Nor are they moralizing images that urge us to undo the 'deconstruction' of the panda. Instead, they lead us to ponder exactly how we are connected to pandas, and how they are connected to the world around them.

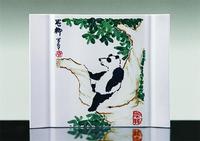

Consider, for example, works like Climbing Up Higher and Higher (2012) or The More One Eats, the Tastier It Becomes (2012). Both of these ceramic works suggest the lighthearted character of the panda, engaged in activities (climbing trees, eating bamboo shoots) that strike the viewer most immediately as carefree and even childish. However, both also depict a state of deep absorption in these activities—an absorption further reinforced by the titles given to the works, which suggest repetitive, ongoing action ('higher and higher'; 'the more one eats'). This depiction of repetitive action has a twofold effect: it both hints at the supposedly instinctual behavior of animals, which repeats according to a kind of objective necessity (for example, for food), and at the stubborn and inaccessible interiority of subjects absorbed in habitual practices. In these works, the panda as a sign or symbol (the loveable and iconic animal that serves as the logo for the World Wildlife Fund) is juxtaposed against the panda as an animal with its own cycles of activity, sustenance, and enjoyment. Even the framing of the ceramic plate as a medium works to suggest the isolation of these vignettes, an isolation which in turn projects the universality of the panda's condition. This isolation exploits the possibilities of the panda as an open sign, a floating signifier that has no fixed signified, and performs a kind of decontextualization.[8] However, at the same time, Lo Ch'ing's pandas constantly escape attempts to transform them into nothing but signs: they live an embodied life and their repetitious activity can only be partially grasped by semiotics.

Indeed, these small scenes, imagining the day-to-day existence of the animal, have the effect of "usher[ing in] new intimations…out of the tedious and mundane world" (as Lo Ch'ing puts it).[9] It is precisely the apparent mundaneness of the panda's existence that prompts the viewer to consider comparisons with human existence in the contemporary moment, to consider the way human lives are bound up with nonhuman lives, even if our signifiers can seemingly float free from 'nature.' If the animal often appears to reflect the human in Lo Ch'ing's paintings, there is also the sense in which the human (as a sovereign, meaning-bestowing subject) gradually disappears from the purview of the artwork.

In Chinese painting, the artist is often considered to perfect the depiction of a particular subject (such as bamboo) when the artist ceases to look at it and actually becomes the subject he or she paints.[10] A parallel process occurs in Lo Ch'ing's images of the animal: as the viewer considers the animal, he or she becomes more and more closely connected to it, until eventually there is only the animal. This move from consideration to complete absorption is evident in a work like Nostalgia, where an emotive state of temporal and spatial disjuncture is seemingly attributed to a panda sitting in the crook of a tree branch. The work is an invitation not to the kind of kitsch nostalgia of late capitalist consumption, but rather to a nostalgia that—intertwining the natural and the cultural—envisions a nonhuman yearning for the past expressed in both mental and embodied contemplation. We, as viewers, can imagine a whole set of things for which the panda might be nostalgic: a home, a family, a time before its own 'dissociation of sensibility.' In any case, however, this nostalgia gestures at worlds beyond human desires and sign-systems, at a deeply vital nostalgia present in the communion of the animal with the tree in which it sits: 'nature' separated from itself yet searching for itself.

In an interview conducted as part of the research for this exhibition, Lo Ch'ing discusses his depiction of the panda in relation to the history of animal painting in Chinese art. He explains that,

Panda is not only a symbol for peace, there's also a kind of Confucian spirit there. Of course, the panda is also a symbol for environmental conservation, which moves away from this idea of prosperity and good wishes … and [towards a] more contemporary positive way of thinking and saving the environment. And so I use the panda, dramatize it, asking the panda to impersonate some human characters, like the Buddhist monk or Confucian scholar, or ecologist or biologist…. And so the panda, in my painting, performs all kinds of activities, to symbolize or present a new world and new intellectual activities in the 20th or 21st centuries.[11]

The panda in Lo Ch'ing's painting forces us to think the nonhuman, and our relationship to it—to take responsibility for thinking in new ways to meet the conditions of the Anthropocene.

[1] Lo Ch'ing, "Panda, A Pensive Confucian Gentleman of Our Times," 6.

[2] Ibid., 7.

[3] Thusly does Paul Manfredi summarize Lo Ch'ing's own assessment of the contemporary artistic moment in which he lives and works. See Manfredi, Modern Poetry in China: A Visual-Verbal Dynamic (New York: Cambria, 2014), 72.

[4] As Robert W. Duffy notes, Lo Ch'ing "is concerned about the natural world and the effects of technology on it." (See "Lo Ch'ing Distills the Essence of Our Time," St. Louis Post-Dispatch, May 2, 1993.) That is, his art understands the mediating role of technology in any representation of 'nature'—it does not presume to go back before technology, but to consider technology's ontology intertwined with nature.

[5] Though, importantly, language (and art) do not give us direct access to any unchanging essence or nature in this extra-linguistic world. At best, they can show us the depths of what we cannot concretely know about things. This does not mean, however, that we are not connected to these things. Far from it: the condition I am describing is premised upon our unavoidable entanglement in things, but in such a way that knowledge of their truth is never applicable.

[6] Ian Bogost, Alien Phenomenology, Or What It's Like to Be a Thing (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2012), 6.

[7] Jane Bennett, Vibrant Matter: A Political Ecology of Things (Durham: Duke University Press, 2010), 120-122.

[8] Lo Ch'ing discusses the tension between the inherited tradition of graphic signifiers and the possibilities for the contemporary artist to work with "unbound" signifiers in his unpublished essay, “Signifier Bound and Unbound: The Relationship between Text and Image in Contemporary Chinese Literature and Painting,” March 1993, written during his time as a Fulbright scholar-in-residence at Washington University in St. Louis. I would like to argue that while this tension relates directly to his appropriation and integration of different aspects of the Chinese tradition, it also functions analogously in the context of his work's navigation of nonhuman signifiers.

[9] Lo Ch'ing, "See a Cosmos in a Vignette" (Taipei: 99 Degrees Art Center, 2010), 5.

[10] For a succinct summary of this idea of Chinese art's communion with the natural world, and its transcendence of the Western subject-object dichotomy, see Simon Leys, The Hall of Uselessness: Collected Essays (New York: The New York Review of Books, 2013), 338-343.

[11] See the interview transcript included as part of this online exhibition.