Introduction

Because I… have everything to do/ with your life and death/ in the future.—Lo Ch'ing, from "O' Panda an' Man"

My younger brother and sister ran up to me/ Arguing, "How should we write the character 'tree'?/ How many strokes?/ How difficult is it?"—Lo Ch'ing, from "The Writing of the Character 'Tree'"

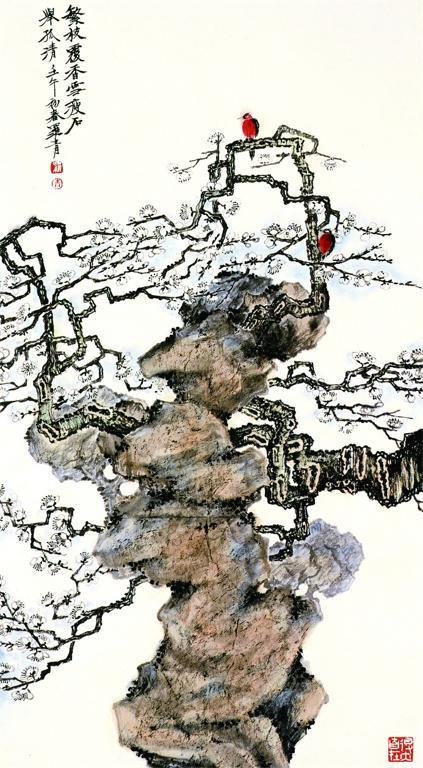

Scholar Joseph R. Allen has suggested that the poet-painter Lo Ch'ing's uniquely postmodern aesthetic is most evident in the artist's ironic deconstruction of linguistic and visual paradigms, in his playful synthesis of Eastern and Western poetic traditions.[1] This is certainly true, but the project of deconstruction in Lo Ch'ing's art is not merely one of words and images. It is also one of beings and vitalities, a project aimed at complicating the understanding of humankind's connection to the world around us. In its kaleidoscopic combination of artistic traditions, Lo Ch'ing's interpretation of the Chinese landscape tradition also serves as a critique of the global (no longer merely Western) metaphysics of environmental objectification. His art asks us to look beyond the instrumentalization of nature as a resource and to recover other ways of imagining life and change.

This essay—and the accompanying virtual gallery—invites viewers to consider Lo Ch'ing's work from the standpoint of a post-metaphysical ecocriticism, to read his postmodern tendencies as part of a broader aesthetic engagement. This engagement transcends East and West in its global significance, offering us new ways of thinking about how we live together with the multitude of entities with whom we share the world and modeling a posthuman ethics of the Anthropocene. The Anthropocene is the name commonly used to describe the era in which humanity has become the single driving force behind major environmental changes that affect the entire globe: climate change, habitat destruction, and the extinction of species, for example.[2] This is the era in which we live, and it is an era that—alongside the effects of global capitalism—obliterates the geographic dichotomies that once shaped geopolitics as well as culture. It is an era in which the human and the nonhuman have become interrelated to an enormous degree, and Lo Ch'ing's art speaks to the many facets of this condition. From his ceramics illustrating the lives, affections, and desires of pandas to his paintings juxtaposing of the time of cities with the aging of great and ancient trees, Lo Ch'ing's art forces us to move beyond our own subjectivity and occupy the position of the nonhuman in the network of contemporary life.

However, his art is no mere invitation to a naïve 'return to nature,' for the disruptive thrust operative in Lo Ch'ing's painting will not allow any such straightforward romanticization of the world around us. Even as he brings together the traditions of Chinese poetry and painting, he also speaks to the contemporary practices that threaten us and our environment. As his poem on the panda (quoted above) suggests, the nonhuman lives that surround us have everything to do with our life and death in the future. As is often the case in classical Chinese literature and art, this premise results in a certain anthropomorphization of nature: nonhuman beings become active interlocutors, seeing us, speaking to us, lulling us to sleep and awakening us. This anthropomorphization is, to a certain extent, however, necessary for us in turn to make ourselves one with the aesthetic subject of our contemplation. Lo Ch'ing's poems and paintings invite us to think long upon—and in thinking upon, to think with, to think like, and to become—birds and pandas, trees and blossoms. Here we arrive at the deeper deconstructive path of Lo Ch'ing's poem-paintings. They lead us to new kinds of thought, to animal-thought and plant-thought, to something "complicated, yet simple and clear"—life as a universal phenomenon.

This essay focuses on three themes found in Lo Ch'ing's poem-paintings included in this exhibition: (1) the figure of the panda as a reflection and critique of human community in dialogue with nonhuman elements of the environment; (2) the depiction of nonhuman temporality, which figures the passage of time as partially interior phenomenon rather than simply an exterior play of appearances; and (3) the often schizophrenic merger of times and spaces that belong to both the depths of the past and the dynamic tensions of the present moment. The works presented are diverse and aim—in the spirit of ecocritical ventures inspired by both Eastern and Western traditions—to broaden the understanding of our own identity and responsibilities in the emergent web of the Anthropocene.

[1] "The Postmodern (?) Misquote in the Poetry and Painting of Lo Ch'ing," World Literature Today 65:3 (Summer 1991): 421-426.

[2] For a succinct overview of the Anthropocene and its effects on visuality, see Emmelhainz, Irmgard, "Conditions of Visuality Under the Anthropocene and Images of the Anthropocene to Come," e-flux 63 (March 2015), http://www.e-flux.com/journal/ conditions-of-visuality-under-the-anthropocene-and-images-of-the-anthropocene-to-come/ (accessed March 20, 2015). In his synthesis of elements of the Chinese painting tradition—as well as tropes of Western critical discourse—Lo Ch'ing's work obviously also engages with the possibilities of vision in the contemporary global moment.